Recently, I finished reading the book, Fermat’s Last Theorem by Simon Singh, and loved it a lot. This is the first book I have completed in a long time, so that felt good. It’s also the first time I have read a book related to mathematics which is not a text book. Actually, the book is very far from being a text book. It’s a fun and interesting read about a theorem which was noted down in 1637 but proving which took mathematicians more than three centuries. For all these years, many mathematicians made it their life’s aim to prove this theorem but were unsuccessful. The book is a story of this journey full of interesting twists and turns. It also made me realize why I loved mathematics so much in school, especially before Greek alphabet took over and numbers became rare in maths classes.

Who was Pierre de Fermat?

The journey starts with Pierre de Fermat who was a judge in the Parliament of Toulouse in the 17th century, one of the high courts in France. He was also a part-time mathematician and after doing his duties for the day, he would come back and just play around with numbers and come up with theorems in his free time. Fermat is remembered as one of the greatest mathematicians of his time, despite his “amateur” status as he was not a full time academic. He was also quite unique in his ways. Publication and recognition meant nothing to him and he was satisfied with the simple pleasure of being able to create new theorems undisturbed. When he would show his work to other mathematicians, it was also mainly to tease them. He would write letters to his British counterparts stating his most recent theorem without providing the accompanying proof. Then he would challenge his contemporaries to find the proof. He also had his own practical reasons for not publishing full fledged proofs. As Simon writes, “First, it meant that he did not have to waste time fully fleshing out his methods; instead he could rapidly proceed to his next conquest. Furthermore, he did not have to suffer jealous nit-picking. Once published, proofs would be examined and argued over by everyone and anyone who knew anything about the subject.”

Fermat’s bold claim

Around 1637, as he was working with his copy of an ancient Greek text, “Arithmetica” by Diophantus, he wrote a theorem in the margin of the book, which came to be known as Fermat’s Last Theorem. The theorem is actually pretty simple to understand. To understand Fermat’s theorem, let’s first look at another theorem which you would have probably read in school called Pythagoras Theorem. Pythagoras’ theorem states that in a right-angled triangle, the square of the largest side is equal to sum of square of other two sides. The numbers which satisfy this condition are known as Pythagorean triples. For example, 3, 4, 5 is a Pythagorean triple where square of 5 (25), equals the sum of square of 3 (9) and square of 4 (16). Similarly, you can come up with many such Pythagorean triples or more generally, you can find an unlimited combinations of a, b and c where

\[a^2+b^2 = c^2\]Now, Fermat built on top of this. He took the following equation which seems very similar to the Pythagoras theorem:

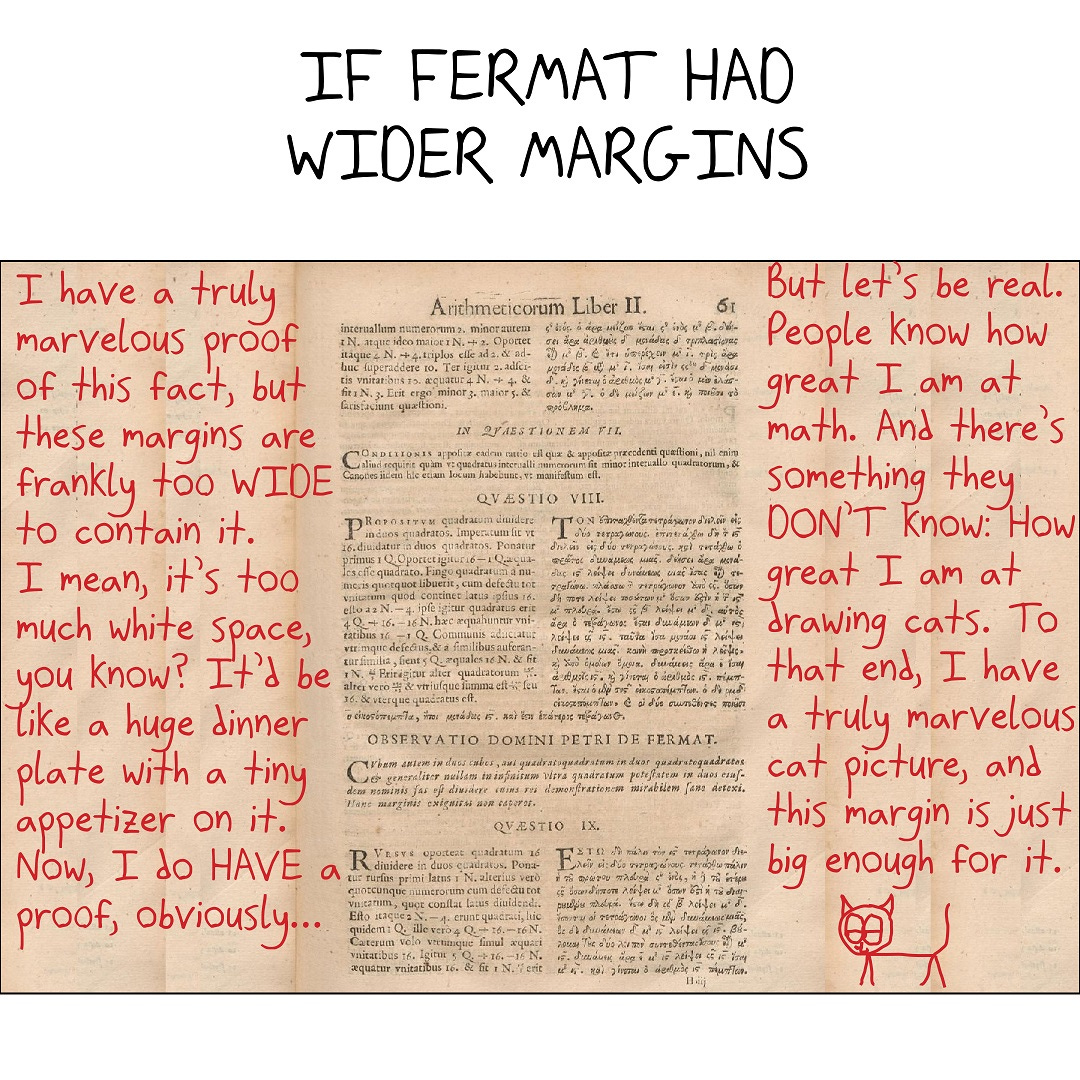

\[a^n+b^n = c^n\]He said that if n > 2, you cannot find any combination of a, b and c which satisfy this equation for a, b and c being positive integers (like 1, 2, 3, 4 etc.) This is actually a very powerful statement. We already have a proven theorem that for n = 2, we have an unlimited number of combinations of a, b and c. Here, Fermat was claiming that you cannot find any such combinations for any other n greater than 2 that you can think of (Feel free to try some combinations). In his typical fashion, he also wrote that he had discovered a “truly marvelous proof” of this proposition that was too large to fit in the margin. Many mathematicians after him tried to find an example that would prove Fermat wrong but they couldn’t find any. So, people started assuming that Fermat’s claim is true but without a formal proof, mathematicians wouldn’t count this as a theorem.

Over the years, there have been various memes about the this theorem. Source: Mathwithbaddrawings

Mathematicians and Their Precision

Mathematicians are well known for being super precise and requiring nothing less than absolute proofs before accepting any statement. Their reputation is clearly expressed in a story told by Ian Stewart in Concepts of Modern Mathematics:

An astronomer, a physicist, and a mathematician (it is said) were holidaying in Scotland. Glancing from a train window, they observed a black sheep in the middle of a field. ‘How interesting,’ observed the astronomer, ‘all Scottish sheep are black!’ To which the physicist responded, ‘No, no! Some Scottish sheep are black!’ The mathematician gazed heavenward in supplication, and then intoned, ‘In Scotland there exists at least one field, containing at least one sheep, at least one side of which is black.’

In some cases, mathematicians have been right to be suspicious. In the seventeenth century, mathematicians showed by detailed examination that the following numbers are all prime: 31; 331; 3,331; 33,331; 333,331; 3,333,331; 33,333,331. As a reminder, prime numbers are those who have no other factors apart from 1 and the number itself. For example, 23 is not divisible by any other number, apart from 1 and 23, and hence, it’s a prime number. On the other hand, we have a number such as 22, which is divisible by 2 and 11, apart from 1 and 22. Hence, 22 is not a prime number. Coming back to the pattern, the next numbers in the sequence became increasingly huge, and checking whether or not they were also prime would have taken considerable effort. At that time, some mathematicians were tempted to extrapolate from the pattern so far, and assume that all numbers of this form are prime. However, the next number in the pattern, 333,333,331, turned out not to be a prime:

\[333,333,331=17×19,607,843\]Another good example where the suspicion was justified is Euler’s conjecture. You might have heard about Euler in school mathematics as well. Euler is considered to be someone who created mathematics than anyone else in history. He also had a conjecture (a statement which has not yet been proven or disproven is referred to as a conjecture) very similar to Fermat’s. Euler’s conjecture states that there are no positive integers a, b, c, and d such that:

\[a^4+b^4+c^4 = d^4\]For two hundred years, nobody could prove Euler’s conjecture, but on the other hand, nobody could disprove it by finding a set of numbers which satisfied this equation. First manual searches and then years of computer calculations failed to find a solution. Lack of a counter-example was strong evidence in favor of the conjecture. Then in 1988, Naom Elkies of Harvard University discovered the following solution:

\[2682440^4+15365639^4+18796760^4=20615673^4\]Not easy to guess at all! Anyway, there was some suspicion about Fermat’s theorem also that just because no one had been able to find a solution, it didn’t make the statement true for all possible values.

I’ll stop myself here and not give away the finale of the book or the theorem. I would highly recommend you to read it though. The book has many interesting stories such as what are friendly numbers, how the number 26 is indeed special, and of course, many more incidents related to Fermat’s last theorem, including how it once saved someone from committing suicide! Simon’s writing is also very easy to follow, and if you don’t have a hatred for mathematics, I think you will enjoy this book.